Los Angeles & Mount Washington Incline Railway

The story of "Florence and Virginia"

Anyone coming to Los Angeles for the first time is amazed to note that Los Angeles is not flat, but instead it is a slanting basin encircled by the Santa Monica Mountains to the west, the high San Gabriels to the north, and the Puente Hills to the east. Within this basin there are a number of small hills which break up the whole area into hills and valleys.

This is a story of one of these hills, Mt. Washington, which is 940 feet in height. It is located on the eastern edge of downtown Los Angeles and on the east shore of the Los Angeles River, running north toward the City of Glendale. How the hill got its name remains somewhat unclear. One would think it was probably named for General George Washington. On what I believe is good authority, I was told it was named for Colonel Henry Washington, who came to Southern California in 1855 to survey the base lines.* He spent a great deal of time in Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties, and supposedly surveyed the Los Angeles River.

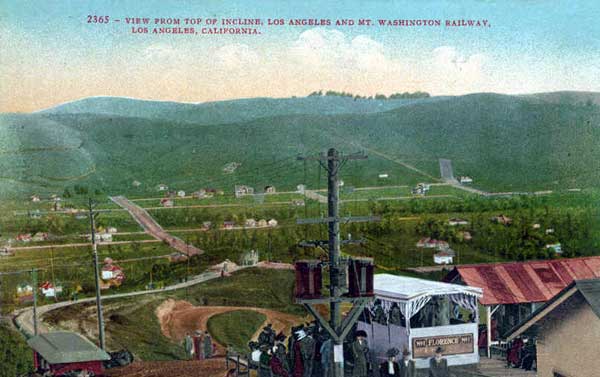

The turning point for Mt. Washington came in 1909, long after the land boom of the 1880's, with the construction of a hotel on the summit and an incline railway by which to reach the hotel and subdivision. The modest hotel took full advantage of the panoramic view from the summit. It was the hope of the developer that people would ride from downtown on the Los Angeles Railway, get off the trolley at Avenue 43 and Marmion Way, and ride the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington Incline Railway to the summit, where they would experience the breathtaking view, whether day or night, resulting in the purchase of a lot. The ploy worked; Mt. Washington became an exclusive and highly desirable hilltop residential site for those who wished to experience a special situation.

Most of the hills of the Los Angeles basin were sparsely settled, primarily due to the initial lack of accessibility. Mt. Washington was no exception. Originally, the hill was once a part of the huge and sprawling Rancho San Rafael and its only residents were some 15,000 sheep. Its slope on the east, west and south sides were rather steep; on the north, however, it sloped down gently.

During December 1894, the los Angeles Consolidated Electric Railway ran a streetcar line from downtown, heading east on North Broadway, crossing the Los Angeles River, then running northeast along Figueroa and Marmion Way to the real estate development of Garvanza at what is today York Boulevard and North Figueroa. Once public transportation was established in the area, the Highlands, now known as Highland Park, blossomed into one of Los Angeles' first streetcar suburban developments of the early 1900's. Although a few homes were built along the base of Mt. Washington, prior to its development the only denizens of the summit were squirrels, quail, rabbits and a few hikers and picnickers. To build a road to the summit would have cost a fortune just to blast out a right-of-way that would be needed for horse and buggy. It was just too steep for streetcars, so the summit remained unsettled for years.

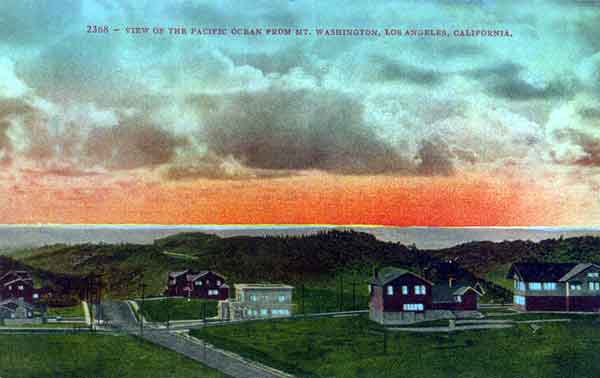

Real estate developer Robert Marsh, of Robert Marsh & Company, had often looked at Mt. Washington as a possibility for real estate development. He believed there was an opportunity to subdivide the somewhat level land at the top into large lots that would have an unsurpassed view in all directions. From the summit one could see the ocean, Catalina Island, and the beauty of the San Gabriels, especially in the wintertime with a white mantle of snow on its peaks. These lots would be expensive, the tract very exclusive, and it would feature elegant homes to rival the mansions on South Broadway, Westlake and West Adams.

Angels Flight began running on December 31, 1901. It operated on a 335-foot track, up a constant 33 percent grade, and ran between Hill Street and Olive on Bunker Hill. Riding Angels Flight gave Marsh an idea. Why wouldn't an incline railway, similar to Angels Flight, be a natural to gain access to the summit of Mt. Washington? Obviously it would have to be a counterbalance cable car system consisting of two cars, one going up, one coming down, and passing in the middle. The only drawback was buying the hilltop, constructing a cable railway, building a hotel at the summit, designing a tract, and installing public utilities. This proved to be more than Robert Marsh & Company could handle. A silent partner was needed to finance the project. Electrical equipment manufacturer Arthur St. Clair Perry became the catalyst to bring the project to fruition.

Robert Marsh & Company, located at 140 West 5th Street in the heart of the financial district, set out to buy the mountain top. The southern two-thirds of Mt. Washington was owned by A.H. Judson and George W. Morgan. They had purchased this from William Hunter in order to build the Highland View Tract, which extended from present day San Fernando Road and Pasadena Avenue (North Figueroa) to the hill. The less desirable northern portion of Mt. Washington was still owned by William Hunter. Neither developer ever considered building up the slopes or constructing a road to the summit due to the colossal costs in hacking out a roadway. After all, a developer was out to make money, not spend it needlessly.

In order to develop the summit, it was necessary to build the cable incline system first. The best access to the top was from the east side, even though it was the steepest. This decision was made because along Marmion Way was the trolley line of the Los Angeles Consolidated Electric Railway. Needless to say, transportation was a must if they were to bring land speculators to the tract site. Although surveys were made from all sides of the mountain, the Marmion Way route, and up what would become Avenue 43, proved to be the most advantageous route. Application for a franchise was submitted to the Board of Public Utilities during April 1908. Shortly thereafter, the proposed drawings were submitted to the board. A 25-year franchise to build and equip the cable incline was granted sometime during the month of May 1908. E.S, Cobb, construction engineer and architect, completed his engineering drawings in July. It was estimated that the line should be in operation by the end of the yean.

The original plans called for an open cable system that more or less followed the terrain of the land. The cable would be situated in a concrete trough that supported the ties carrying the rails. The length of the cable system was 3,000 feet and in places the grade ran as high as 42 percent. An ideal system would have been a straight line from Marmion Way to the summit with the rails and cables carried on a trestle system. Such a line would have cost over $100,000, whereas following the near contour of the land would be in the neighborhood of $27,000. This figure also included the winding machinery, the two cable cars, the cable, and the control house at the top.

Actual construction began during October 1908. The newspapers of the time do not specify a date. The Mercereau Bridge Construction Company was awarded the construction contract. Grading and concrete work began. A concrete trough was built up the mountainside to conceal the cable. By the end of the year the work was already a month and a half behind schedule.

It was reported in the January 3, 1909 issue of the Los Angeles Times that only half of the roadbed had been completed. During the week of January 5th, the machinery for the power

plant, the winding gear and the cable arrived and was pulled up the grade by block and tackle. It took four days to inch the

equipment up the hillside.

Another starring date was set. Why not open the line to Mt.

Washington on Washington's birthday - February 22nd? It was announced in the Times that a big celebration would be

held at Mt. Washington on Washington's birthday and there would be free rides. Such a celebration never took place. A two-week rainstorm, during the latter part of January and into February, hit the entire Southern California region. Although the roadbed was not washed out, the workmen were unable to work during the heavy downpours. Once things dried out, the ties were installed, the rollers for the cables were placed, and the power plant building completed. By February 10th, the electricians were working on the control system and mechanics were getting ready to run the cable down to Marmion Way for the cable loop. Then the rains returned. Little work was done the balance of the month, except for work inside the cable power house.

Slowly, things began to fall into place. In early March the cable was wound down the hill, placed under the cable rollers and tied to the two cars. The cable powerhouse was turned on and everything worked fine. The cable cars, which arrived March 4th, were built by the Llewellyn Iron Works of Los Angeles, a local elevator builder. In fact, Llewellyn held the contract for the two cable cars and all the electrical operating equipment. On March 30,1909, the power was turned on, the machinery tested, and the two cars slid up and down the slopes of Mt. Washington like a charm.

On April 2, the city inspector came out to check the completed

construction. He was there to see if everything was built according to plan and that the equipment met all city requirements. The man worked all day, making notes, watching it in operation, and even riding up and down several times. A week later Robert Marsh & Company received a long letter from the city engineer which stated that to guarantee the highest efficiency and safety to the public the entire cable route would have to be wood planked. The city engineer cited that at the time of inspection it was observed that when the cable machine was set in operation, and placed in tension, the cable, itself, rose to such an extent that if a person were to cross or walk the route, the change in cable tension could easily cut off a leg. With homes scheduled to be built on the slopes, and

with children no doubt playing in the area, it would be too dangerous to authorize approval for operation as the line was presently built. Wood decking of the entire cable route would eliminate this hazard. The decking expense was another $15,000, bringing the entire cost of the incline to $42,000. A far cry from the proposed $27,000.

A wood deck was immediately installed since there was no alternative or the whole thing would have been for naught. Operating tests with the incline cars began May 2, 1909. Local engineers carried out numerous safety and stress tests. One such test involved the loading of each car with sacks of sand that would be equal to or more than the weight of fall load of passengers. The tests went perfectly as the powerhouse and winding machine worked well. The line was declared completed. The city inspector was called to give.his final approval. With the city's final OK the official opening date was set for May 24,1909. John Marsh & Company placed advertisements in the Los Angeles Times inviting the general public to come see the new incline railway and to ride it to the summit of Mt. Washington. An ad for May 21st stated:

| Mt Washington is just 20 minutes from Broadway and the center of downtown Los Angeles. It is no longer a dream of future achievement. It is a splendid, vivid reality of today. The stately mountain, whose beauties and scenic advantages have been admired for years, is now within 20 minutes of the heart of the business district. The sound of builders is heard from every side. Beautiful costly homes are about to spring up all over the mountain. A magnificent system of streets and boulevards is being projected. A trip to the incline and the summit of Mt. Washington will inspire and thrill you. Just take the Garvanza car, get off at Marmion Way and Avenue 43, and for 5 cents, just a nickel, you will have the ride of a lifetime. Service begins Sunday- May 23rd. Robert Marsh & Company 140 West 5th Street-Los Angeles |

Beginning on Sunday, May 16th, Robert Marsh & Company began to publish a Sunday supplement to the Los Angeles Times entitled the Mt. Washington Eagle. It was a two-page affair inserted into the Times, and it. was published every Sunday for a two-year period. The idea was to attract prospective buyers to view Mt. Washington. It had features on the building and operation of the incline, details of a proposed grand hotel to be built on the summit, real estate tract maps, sample drawings of proposed homes, etc. Apparently it worked, as the people came in droves for the first official day of operation, Sunday May 23.

The preceding Saturday's Los Angeles Times carried the following story:

| Since its completion, two weeks ago. it has been put through every rigid test known to the engineering profession. Immense loads of sand have been repeatedly carried up and down without taxing the mechanism. The cars seat 24 people, but have a maximum capacity of 3O passengers. It takes the car less than five minutes to go from the terminal at Marmion Way to the summit. A unique feature of the Mt. Washington Incline is the telephone connection. Each car is equipped with a phone and the conductor is a!ways in communication with the engineer in the powerhouse above. The conductor in charge of the cars is H.B. Fox, a former Southern Pacific conductor. C.L. Meyers, a mechanical engineer, is in charge of the powerhouse and winding machinery. The line has horizontal and vertical curves requiring the greatest possible skills in planning and erecting. The first run will run tomorrow at 7:00 A.M. and will operate all day until 6:00 PM. The view from the summit is spectacular. |

All day Sunday, each Garvanza car was loaded to standing room only. The Los Angeles Consolidated Electric Railway was not prepared for such an event. People lined up at the end of the cable line all the way down Marmion Way, clear to Pasadena Avenue, in order to make the trip. A car left the terminal every 10 minutes throughout the day. The passenger count that day never appeared in the papers, but it must have been at least 3,000, as people were seen hanging on to the sides of the 24-passenger cable cars.

The Llewellyn cable cars were rather unique. Each car seated 24 passengers comfortably and could accommodate at least six standees, and all those who could grab on. Marsh decided that it was not safe for hangers-on or standees and issued orders that the car would not start until every passenger was in a seat. However, when no official was around, the order was often overlooked as it might be a 20 to 30 minute wait before the next car up the hill. When the line opened the cable cars had a solid roof. These were later removed and replaced with a roll-hack canvas roof. The reason for this change is unknown. The cars were painted a bright fire engine red. The front of each car was designated as the "LA & Mt. Washington Ry. Co." Each car was equipped with a telephone. The telephone must have been sound powered, and the wire run on a pulled wire system strung along the cable track. At first the cars had a trolley bell on the roof. It is assumed that by ringing the bell the conductor would inform passengers at the Marmion Way and the summit terminal when the car was about to start.

The line was built to a gauge of3 feet 6 inches, The whole line had three rails from Marmion Way to the summit, except for the passing oval at the center where there were four rails. Each car stayed either on the right or left hand side of the track. sharing the same center rail.

The powerhouse was run by a 3-phase Westinghouse Electric induction motor It was rated at 40 horsepower. The motor drove a bull wheel of about three feet in diameter and mounted level. The power was controlled by a standard trolley car controller. The only difference was that the resistance coils, normally mounted under a trolley car; were placed high on the wall of the powerhouse, allowing any heat to escape, so it would not overheat the motor room.

The 40-horsepower motor was rated at 720 rpm's. It was geared down by two sets of gears having a ratio of 25:114 and 14:44. The cable cars could be inched down a little at a time or attain a maximum speed of4 mph, about the speed of an elevator. The main shaft supported two sets of 48 inch pulleys. One set consisted of the bull gear wheel with a sleeve on each side, and the other pair had a second smooth flared wheel that served as a massive brake drum. The main cable, passing through the drive mechanism was a 7/8-inch steel crucible steel cable with a breaking strength of 52,000 pounds.

Should a cable break, which was highly unlikely, a bronze wedge served as an emergency brake the minute slack showed up. It not only stopped the pulley, but forced the cable to the bottom of its groove and seized it, so that if the cable did break, the other half would be secure. It was a very remote possibility that the cable would break on both sides.

The engineer, stationed in the powerhouse, was capable of controlling the loading at the summit and collecting of the fare for passengers going down. However, he didn't. The lower terminal was controlled by the conductor who advised the engineer by phone when his car was loaded and ready to go. Since the descending car was without a conductor, the conductor on the upward car would hop across from the step of his car to the one descending and collect the tickets.

The cars began operations at 7:00 A.M. and ran until 6:00 P.M. The schedule called for 20-minute service, but on busy days the cars would run up the hill, unload, and immediately return for another load. The fare was five cents each way. Later, residents were able to purchase ticket books which allowed them to ride for 2½-cent per ticket. Traffic was so heavy that on weekends the car started at 6:00 A.M. and ran until midnight. All kinds of tourists came to see the lights and lovers soon found the area to be very romantic.

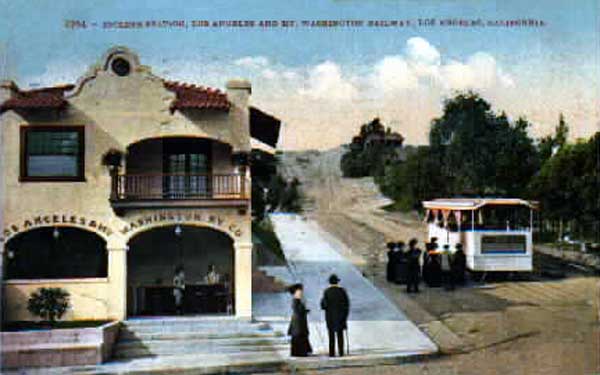

During the Elks National Convention, held in Los Angeles during the second arid third week of July 1909, the Los Angeles Times reported on July 18, that over 10,000 Elks had visited the summit of Mt. Washington during the past week. It quickly became obvious that some sort of shelter was required at the lower terminal at Marmion Way and Avenue 43. In case of rain there was no place to get under cover. Architect Fred Dorn designed a two-story mission style station for the site. The ground floor was to contain a waiting room and ticket window, and the upper floor was to be the residence of the ticket seller. The station was completed and placed in service on November 1st. At the foot of Avenue 43 was a covered over pit enclosing the apparatus which returned the cable, and a machine that took up the slack in the cable itself. For three blocks upward from Marmion Way and Avenue 43, the cable was buried in the street instead of under wooden planks.

While the cable incline was under construction, the surveying for the real estate tract was taking place. It was decided to have a center main street running north and south with side streets going east and west. The center or main street was named San Rafael Avenue. Although Mount Washington had been a part of rancho San Rafael, the street was named in honor of the hometown of financier Arthur St. Clair Perry, San Rafael, California. San Rafael Avenue would run nearly a mile along the summit of the mountain. Lots were to be as large as two acres to as small as villa lots 75-feet wide to 175-feet deep, with some of the back yards running down the slope of the hill. Each lot was to have the purest water piped in from a company owned water supply. A reservoir was built on the northern end of the summit with a storage capacity of over 350,000 gallons, The reservoir was eventually covered with a wooden roof. Apparently kids were using it as a swimming hole. Huge letters reading

MT WASHINGTON

were fastened to the top of the roof. Water was pumped up the hill from a natural spring located alongside the Santa Fe Railway tracks at Avenue 41. The pump still feeds the Mt. Washington reservoirIn addition to the incline railway, a road to the summit was also required. While they were building the incline, a road was being carved out of the mountainside. It took off near Avenue 41 and wound around the side of the hill for nearly a mile before reaching San Rafael Avenue. It was named Mt. Washington Drive. In due course, the drive was oiled and cement curbs were provided. It was also planned that in the future they would continue Mt. Washington Drive across the summit and down the west side of the hill, ending at the Los Angeles River basin. The cost of building Mt. Washington Drive was S125,000.

Electric power was provided by Henry E. Huntington's Pacific Power & Light Company. P.P.& L. also installed ornamental street lights on poles 30 feet in height. During October 1909, the Los Angeles Gas & Electric Company had a force of men at work laying a gas line all over the mountaintop. It was quite a task to run the gas lines up the hill and to each lot.

One issue of the Eagle stated that the man who buys a lot or home on Mt. Washington has these advantages:

- Absolute freedom from noise or smoke.

- No undesirable residential element.

- The grandest views of mountain, valley, and the sea,

- Pure mountain air, high, dry, and sanitary.

- An environment of public and private improvements.

- The grandest water found in Southern California.

The December 12, 1909, issue of the Eagle, appearing as a supplement to the Sunday Times, stated that all the completed homes had been sold. They were purchased by:

- J.A. Merrill - a real estate man

- A. Holtby Meyers - a real estate man

- W.J. Shelley - secretary of the Owens River Association

- C.W. Hall -general manager of Braun Chemical

- A.P. Bond - president of Bond Baking Company

- W.C. Eisenmeyer - manager of the Los Angeles Ice & Cold Storage Company

The incline and Mt. Washington Drive were not intended just to serve the residents and the seasonal tourists. They were all part of an overall promotional program to establish a mountaintop resort which included a hotel, magnificent gardens and sporting facilities. The May 9th Eagle announced that the contract had been let to the Milwaukee Building Company for the building of the Mt. Washington Hotel. This was a local firm operated by Meyer & Holler. Among their works were Grauman's Chinese Theatre and the Petroleum Building.

With the contract let, construction began at once on the $40,000 Mt. Washington Hotel. The structure was to be a three story, mission-style building. It would have a roof garden, spacious balconies and porches, and a beautiful Japanese garden out in the front. A porch on the northwest comer would connect with a spacious dining room. On the southwest corner there would be another porch going to a library with a pavilion. A walk then lead to the incline railway station. The hotel, itself, would contain just 18 rooms, each with a private bath. It was rather extraordinary for the time to have a hotel with a bath for each room. The basement was to be used for employee rooms, the heating plant and food storage lockers. Tennis was a most popular sport at the turn-of-the Century. The hotel was to have two tennis courts on the property. The grounds were to be laid out with lawns, shrubbery, trees and graceful winding walkways and drives for those who wished to take a constitutional. In the original plans, the Japanese garden was to have an observations tower in order to have a more commanding view of the mountains, valleys and the sea.

The hotel went up quickly, much faster than the construction of the incline railway. On August 15,1909, the Los Angeles Times reported that the plastering of the interior walls was now in process. The article went on to say, "At the speed of the construction of the Mt. Washington Hotel, it should open on November 15th."

The Los Angeles Times for October 17, 1909, ran a large article on the road to Mt. Washington.

| READY FOR AUTOMOBILES. Since the oiling and rolling of the beautiful Mt. Washington Drive, that thoroughfare is now in splendid shape. The road was constructed at great expense. It is the only road to the summit, except by way of the incline railway. The people gassed up their flivers and came in droves to try their new machines on the mountain highway. A few boiled over, but most made it to the summit. The finishing touches to the Mt. Washington Hotel is progressing nicely. The building occupies what is probably the most commanding site in all Southern California. It should be ready for occupancy on November 15. |

Naturally, November 15th came and went with no grand opening of the hotel! The Times, for December 5, 1909, stated, "Last Saturday over 2,000 rode the incline to see the hotel still under construction, to look at the view, and to inspect the lots. Nearly a like amount traveled the new mountain road to the summit by way of Marmion Way. The hotel itself is in its final touches."

"HOTEL TO OPEN JANUARY 5," stated the Times,' on December 26th. "Hotel Mt. Washington will open January 5, 1910. Managers will be Guy K. and L.M. Woodward. The grounds consist of 14 landscaped acres. The hotel is built to Mission-style with a roof garden. The furnishings include velvet carpets, brass beds, and furniture of oak and walnut. The dining room is operated by a chef of renown." The Times was also premature. The hotel finally opened, apparently sometime during the week of January 23, 1910. The Times does not give an exact date. In any case, the week was scheduled as Mt. Washington Hotel week. People were invited to come see the grand resort hotel. The Times went on to state that: "Lookout Drive is to be opened from Eagle Rock Avenue. Riverside Drive will be continued east from San Rafael Avenue around the Reservoir Hill, San Rafael is to be extended north to the opening of a new 30 acre subdivision north of Reservoir Hill. All the streets will be oiled and will have concrete curbs, gutters and walks." The hotel quickly became a hangout for the rich. It did a good dining room business, and on the weekends the rooms were normally all sold out. On September 3, 1911, the Times stated that the hotel had planned to add 100 rooms and 50 baths. Nothing came of this proposal.

It was reported that the incline station on Marmion Way was so busy that Mr. Simons, a man of much experience, was opening a refreshment stand in the depot. His particular experience in doing what, the Times did not elaborate. Probably opening pop bottles and making hot dogs. In early February it was reported that 3,500 passengers were carried to the summit on a Sunday afternoon. It appeared that Mt. Washington had become the 'in place'. So much so that after the February issue for 1910, the Mt. Washington Eagle insert in the Sunday Los Angeles Times was discontinued. Obviously, the lots were selling very well, as the last issue stated that Mrs. Sally V. Riggins, wife of James R. Riggins, a prominent San Joaquin Valley oil man, had purchased the final lot in the initial tract, Also that W.S. Taylor, a prominent attorney, had purchased the first lot in the Reservoir Tract.

An advertisement in the November 11, 1910, issue of the Los Angeles Times stated, "TAKE AFTERNOON TEA ON MT. WASHINGTON Between 4 and 5 P.M. afternoon tea is served daily in the west lobby of the picturesque Mt. Washington hotel. The scenic ascent of the incline, and the wonderful scenery visible from the hotel make this the most enjoyable trip in Los Angeles. Robert Marsh & Co., 140 West 5th Street, Los Angeles."

With all the resort hotels in Los Angeles and Pasadena, one can only speculate as to how Robert Marsh & Company could make a profit from a hotel with only 18 rooms, even though they had an adjoining bath. Pasadena, itself, was full of large luxurious hotels such as the Raymond and the Green. The Mt. Washington Hotel was off the beaten path and somewhat difficult to reach. Who would come to Los Angeles on the train with luggage in hand, board a streetcar, and head for the Mt. Washington Hotel? Most of the people who did come to Mt. Washington did so by auto or incline, usually only spending the day admiring the view and, at most, probably having lunch.

The background for the Mt. Washington Hotel all came together when I read an old brochure at the Huntington Library which stated that near Sycamore Grove Park there were seven film studios. Apparently, the Arroyo Seco and the surrounding countryside were ideal for film making. At that time all silent filming was done in the out-of.doors. Even indoor scenes in homes, hotels, buildings, etc., were filmed on open outdoor sets. There were no arc lamps back then. The Mt. Washington Hotel became a gathering spot fur celebrities such as Charles Chaplin, who always stayed at the hotel while making a film at Sycamore Grove studios. Other stars of screen and sport also took rooms. So, obviously, the Mt. Washington Hotel was not a transient hotel at all.

In my research of Mt. Washington I found in the Huntington Library, a privately printed book spelling out the early history of the motion picture industry in Southern California. It was entitled The Motion Picture Industry in Southern California, listing no author, but it carried a publishing date of 1918.

In essence it stated that the motion picture camera had its beginnings in 1895, and by 1896 the Vitascope Camera became commercially available. This was the camera that made the flip card motion pictures one used to see in penny arcades. It went on to say that William N. Selig, who had operated traveling tent shows and produced Kinetoscope films for penny arcades, moved from the south to Chicago. In early 1902 he opened up his Electric Theatre which featured silent films. He found the weather in Chicago miserable, and quickly decided to move to Los Angeles where the climate was far better. He hired Francis Boggs and Thomas Person to set up a studio in Los Angeles. They arrived here with a troupe of players and settled in a large building next to Sycamore Grove Park. Here, they built a large outdoor stage with divisions where sets could be set up for room interiors and exteriors, allowing the troupe to move from each division as a continuous picture. The first full-length picture made there was the Count of Monte Cristo. One scene called for the star to rise out of the sea. So the troupe took the Los Angeles & Pasadena electric interurban, which passed in front of the studio on Pasadena Avenue, to Santa Monica. Such was one of the Los Angeles area's film attractions - variegated scenery. The next film was The Heart of a Race Tout, Silent Towers was the leading actress and Charles Durin played the male lead.

Apparently there was no room for growth at the studios, so in 1913 the Selig studio moved to a Los Angeles suburb called Edendale. Edendale became the "Film Capital" before Hollywood took over.

When the film stars left Sycamore Grove Park, it had a devastating effect on the Mt. Washington Hotel. The Los Angeles Times reported in its May 10, 1914 issue:

| MOUNTAIN HOTEL LEASE: -Involving a reported total consideration of $25,000, the Mt. Washington Hotel has been leased jointly to E.P. Reed of Providence, Rhode Island, and to Mrs. L. Sullivan, formerly of Detroit. Negotiations are being conducted by Robert Marsh & Company, principal owners and agents of the hotel. The hotel is reached by the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington Cable Railway which connects with the yellow line. The hotel grounds comprise seven acres of highly visible property and a double tennis court. The lessees have already occupied the premises. Reed is a practical hotel man, having 20 years experience conducting a leading hotel in Providence. Mrs. Sullivan will act as hostess with years of experience at the Cadillac Hotel in Detroit. |

The Times began carrying little advertisements for the hotel such as: "Make Mount Washington Your Automobile Party," with line art showing people climbing Mt. Washington Drive bound for the hotel. Also, people chatting across a well-stocked dining table with the words, "Best breakfast and lunch in town on famous Mt. Washington Drive." It showed a line an scene of people looking off into the wild blue yonder from Mt. Washington with these choice words, "Come see Nature's Masterpiece and dine at World Famous Mt. Washington Hotel." Even with all the publicity, the hotel closed for good sometime during the summer of 1921. The newspapers tell about the closing, and the fact it was being offered for sale, but no date was given.

The Los Angeles City Directory for 1922 indicates that the Mt. Washington Military School occupied the old hotel. In a full page advertisement, it shows a picture of the hotel, describing it as headquarters for the school. The school was established by Colonel William Strover, and the advertisement stated it was "An ideal school for boys and young men in an ideal location. From grammar school through high school. Personal supervision under high-class instructors. Individual instruction if necessary. On a 20 acre campus." Apparently, the Mt. Washington Military School did not last long. Where Colonel Williamson found an additional 13 acres on a nearly sold out hilltop is in question. No doubt a parade ground was located east of the Arroyo which made up the difference in acreage.

In 1923 the Los Angeles City Directory listed 700 Mt. Washington Drive as the location of the Goodrich-Mount Washington Emphysema Hospital. Dr. F. Gilman Goodrich had previously had offices in the Pacific Electric Building at 610 South Main. Next, he had a whole hospital on the summit of Mt. Washington. It appears the respiratory hospital closed in late 1924 or early 1925 for there is nothing in the City Directory in the 1925 edition at 700 Mt. Washington Drive or the San Rafael address. In fact, F Gilman Goodrich is not even listed in the directory at all. So either he took out the kidneys of the wrong patient or married some wealthy one and retired.

In 1925, the vacant hotel was sold to Parmahansa Yogananda, a monk of the ancient Swami Order in India, and founder of the Self-Realization Fellowship. At the time Yogananda purchased the hotel it was full of vagrants and many of the windows had been broken. The hotel building remains as the international headquarters of the Self-Realization Fellowship. Today, it is still a Mt. Washington landmark, although it is walled in. An inspection of the hotel shows that the first floor still has the dignity of a hotel lobby, the library remains paneled wood, and the dining room still has the charm of years gone by.

The Mt. Washington cable incline was closed down for two days starting August 15, 1909, in order to replace the wheels of the cable cars with chilled steel wheels. Apparently, the wheels were wearing down so badly that they caused jostling and jarring of the passengers during passage. The cable rollers were also wearing down unevenly, and they were replaced as well.

The cable cars themselves were generally renovated during October, to such an extent that they hardly resembled their former appearance. The heavy roof on the cars were removed and replaced with an attractive canvas canopy roof. How all this rebuilding was accomplished is unknown, since the cars operated in daily service and there were no replacement vehicles. The exterior red paint was replaced with white.

Following World War I all utility companies came under the jurisdiction of the City of Los Angeles - Board of Public Utilities. This meant that the electric company, the gas company, the telephone company and any elevators in town fell under its control. The BPU made an inspection of the incline. They then wrote Robert Marsh & Company, informing them that the cable was becoming worn and should be replaced. They also stated that a safety cable was required in case the regular cable broke. Marsh's reply to the State Public Utilities Commission was that the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington line was a railroad, not an elevator, and consequently the BPU had no authority in this situation.

Apparently Angel's Flight fell into the Board of Public Utilities trap, but that did not cause the Marsh & Company to follow suit. There appears to have been a running battle between the City of Los Angeles, the California Railroad Commission, and the Mt. Washington incline over who had jurisdiction over the line. In a hearing before the California State Supreme Court, the court it ruled that the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington Railway was a vertical elevator - not a railroad. Marsh stated that it was originally given a license as a railroad, otherwise it would have been called the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington Elevator. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court ruling was not overturned. The incline was classified as a vertical elevator.

On January 1, 1919, the BPU ordered the Mt. Washington incline to close down until it could pass muster. On January 14, 1919, the Los Angeles Times carried the following article:

| "INCLINE RAILWAY TO STAY ON MT. WASHINGTON - A delegation of Mt. Washington residents was before the Board of Public Utilities yesterday to protest against the reported prospective dismantling of the incline railway." On the 9th the board issued an order to the operating company to the effect that if the cable was quickly replaced the road need not shut down. On the 15th of January, the Times called Robert Marsh & Company and spoke to Marsh. Their article said that he had received no orders to replace the cable or to dismantle the railway. |

Without service by the incline, the entire top of Mt. Washington would be completely isolated from the outside world, excepting by automobile. The Los Angeles Railway ran the 'W'-Line car along Marmion Way, the southeast side, and the '5'-Line car ran on the west side of Mt. Washington. It would have been a hefty walk from either service. However, when push came to shove, Marsh just ended it all. it is believed that the line stopped running January 9,1919. There is no record of this in the Los Angeles Times nor the local Highland Park newspaper. No one gave any news of the last run, it just quit.

The only opposition to the abandonment came from the Board of Public Utilities itself. H,Z. Osborne, the director, tried to get the board to issue a temporary order to Marsh to keep the line open until the cable could be replaced. But the board's own mechanical engineer advised that the line should remain closed for safety reasons, even though the whole mountaintop was without any sort of public transportation.

The citizens of Mt. Washington still had faith in the incline railway. Many wrote to the California Railroad Commission asking for the enforced continuance of service, On September 20, 1921, the commission, after a hearing on the matter (Case No. 1619 Walter C. Eisenmayer et al, vs. the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington Incline Railway Company) at which the City of Los Angeles - Board of Public Utilities was represented, decided that the board had complete jurisdiction and therefore, dismissed the complaint.

Upon the suggestion of the Los Angeles City Attorney, the board cited Robert Marsh & Company to appear to show cause why the franchise of the incline should not be forfeited. A hearing was held May 1, 1922, at which all parties interested were requested to be present. A number of attempts were made, both formal and informal, to obtain either a reliable bus service for Mt. Washington or continuance of the cable incline, but no definite result was reached. Thereby, for the reason that no one was willing to take the financial risk, the board, at its meeting of May 8, 1922, ordered the incline to resume service within 90 days or forfeit its franchise. The incline railway was ordered to remove its cars after the 90- day period. Nothing was accomplished; except that the cars were removed. The tracks were not taken up until 1930.

Because of the abandonment of the railway, the City of Los Angeles had to purchase Mt. Washington Drive, a private road, and assume maintenance. Also, they had to build a road down the west side of the hill to Cypress Avenue. San Rafael Avenue was eventually extended north to El Paso Drive and then on to York Boulevard. For the price of building all these roads, they would have been well ahead to have taken over the incline and operated it as a city railway.

As a scenic attraction and as an engineering marvel, the Los Angeles & Mt. Washington Railway provided an interesting chapter in Los Angeles history. There is little remaining evidence of the incline, save for the waiting room and ticket agent's home at Marmion Way and Avenue 43, which has now been remodeled into a private residence. Avenue 43 pretty much follows the incline's path up the hill, and at the summit the old powerhouse has been converted into offices for the Self Realization Fellowship, Today, the Mt. Washington Hotel exists as it did in the past, with the exception of a few interior changes. You still get the feel of the old Hotel. The grounds and gardens are well maintained and visitors are welcome. The tennis counts are in the same location, and the homes on the summit are as stately as when built over three-quarters of a century ago. The reservoir has been converted to two metal tanks, but otherwise one can still see Robert Marsh's influence in the landscape. Take a journey back in time, drive up old Mt. Washington Drive to San Rafael Avenue. Visit the old Mt. Washington Hotel and glance down the old incline's right-of-way. Take a look toward San Pedro; you might even see the S.S. Catalina taking off for that enchanted Isle!